Discrete Mathematics Unit 1 CSE Notes – Sets, Relations and Functions (BEU BTech 3rd Sem)

Complete Discrete Mathematics Unit 1 notes for BEU BTech 3rd semester CSE and CSE AI-ML pdf download. Covers sets, types of sets, set operations, Venn diagrams, relations, functions, cardinality, and basic set theory concepts in simple exam-ready language.

Discrete Mathematics is a core subject in BEU BTech curriculum and is especially important for BTech CSE and CSE AI-ML students in the 3rd semester. This subject helps students develop logical thinking and mathematical foundations that are required in computer science fields such as data structures, algorithms, databases, artificial intelligence, and programming logic.

These Discrete Mathematics Unit-1 notes are prepared strictly according to the BEU syllabus for BTech 3rd Sem, covering all important topics like Sets, Types of Sets, Set Operations, Venn Diagrams, Relations, Functions, and Cardinality of Sets. The notes are written in a simple, exam-ready format, making them suitable for both class preparation and university exams.

For BTech CSE and CSE AI-ML students, Unit-1 plays a foundational role because concepts like sets and relations are directly used in database design, logic building, and AI models. These BTech Discrete Mathematics notes are designed to help students understand concepts clearly even without reference books.

Overall, these BEU BTech Discrete Mathematics Unit-1 notes are ideal for 3rd semester students who want clear explanations, proper examples, diagrams, and exam-oriented content in one place.

Discrete Mathematics unit 1 syllabus

Sets, Relation and Function: Operations and Laws of Sets, Products, Binary Relation, Partial Ordering Relation, Equivalence 6 hrs. Cartesian Relation, Image of a Set, Sum and Product of Functions, Bijective functions, Inverse and Composite Function, Size of a Set, Finite and infinite Sets, Countable argument and The Power Set and uncountable Sets, Cantor's diagonal theorem, Schroeder-Bernstein theorem.

Set

A set is a well-defined collection of distinct objects called elements. Well-defined means it is always clear whether an object belongs to the set or not. Sets are usually represented using capital letters, and their elements are written inside curly brackets. Order of elements does not matter in a set, and repeated elements are not allowed.

Example:

A = {1, 2, 3}

Here, 1, 2, and 3 are elements of set A.

Types of Sets

1. Empty Set (Null Set)

An empty set is a set that contains no elements. It is denoted by ∅ or { }.

Example:

A = {x | x is a natural number less than 0}

A = ∅

2. Singleton Set

A singleton set is a set that contains exactly one element.

Example:

A = {5}

3. Finite Set

A finite set is a set that contains a fixed and countable number of elements.

Example:

A = {2, 4, 6, 8}

Number of elements = 4

Formula:

If a set has n elements, then |A| = n

4. Infinite Set

An infinite set is a set that contains unlimited or endless elements.

Example:

A = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, …} (set of natural numbers)

5. Equal Sets

Two sets are called equal sets if they contain exactly the same elements, regardless of order.

Example:

A = {1, 2, 3}

B = {3, 2, 1}

A = B

6. Equivalent Sets

Two sets are called equivalent sets if they have the same number of elements, even if the elements are different.

Example:

A = {a, b, c}

B = {1, 2, 3}

|A| = |B| = 3

So, A and B are equivalent sets.

7. Subset

A set A is said to be a subset of set B if every element of A is also an element of B. It is denoted by A ⊆ B.

Example:

A = {1, 2}

B = {1, 2, 3, 4}

A ⊆ B

8. Proper Subset

A proper subset is a subset that is not equal to the original set. It is denoted by A ⊂ B.

Example:

A = {1, 2}

B = {1, 2, 3}

A ⊂ B

9. Universal Set

The universal set contains all the elements related to a particular discussion or problem. It is denoted by U.

Example:

U = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

A = {2, 4}

10. Power Set

The power set of a set A is the set of all possible subsets of A. It is denoted by P(A).

Example:

If A = {a, b}

P(A) = {∅, {a}, {b}, {a, b}}

Formula:

If |A| = n, then |P(A)| = 2ⁿ

11. Disjoint Sets

Two sets are called disjoint sets if they have no common elements.

Example:

A = {1, 3, 5}

B = {2, 4, 6}

A ∩ B = ∅

12. Overlapping Sets

Two sets are called overlapping sets if they have at least one common element.

Example:

A = {1, 2, 3}

B = {3, 4, 5}

13. Superset

A superset is a set that contains all the elements of another set. If set A is a superset of set B, then every element of B is also an element of A.

Superset is the opposite concept of subset.

If B ⊆ A, then A is a superset of B.

Superset is denoted by ⊇.

If A contains extra elements in addition to B, it is called a proper superset.

Proper superset is denoted by ⊃.

Examples

Example 1:

A = {1, 2, 3, 4}

B = {2, 3}

A ⊇ B

Read as: A is a superset of B.

Example 2 (Proper superset):

A = {1, 2, 3, 4}

B = {1, 2}

A ⊃ B

Read as: A is a proper superset of B.

Relation with subset (exam tip)

A ⊆ B ⇔ B ⊇ A

A ⊂ B ⇔ B ⊃ A

Important formulas

Number of elements in a finite set A is denoted by

|A|.If

|A| = n, then number of subsets =2ⁿ.Power set size:

|P(A)| = 2ⁿ.

Representation of Set

The representation of a set means the method used to describe or write the elements of a set clearly. A set can be represented in different ways depending on whether we want to list all elements or describe them using a rule.

A set must always be represented in a clear and unambiguous form.

There are two standard methods of representing a set.

Both representations describe the same set, only the writing style is different.

These representations are widely used in mathematics and discrete mathematics.

Roster Form (Tabular Form)

In roster form, all the elements of the set are listed explicitly inside curly brackets.

Elements are separated by commas.

Order of elements does not matter.

Repeated elements are written only once.

This form is useful when the number of elements is small.

Example:

A = {1, 2, 3, 4}

B = {a, e, i, o, u}

Set-Builder Form

In set-builder form, a set is represented by stating a property that all its elements satisfy.

Elements are described using a condition or rule.

This form is useful when listing all elements is not possible.

The vertical bar

|is read as “such that”.

Example:

A = {x | x is a natural number less than 5}

B = {x | x ∈ N, x is even}

Conversion between forms

Roster form can be converted into set-builder form by identifying the common property.

Set-builder form can be converted into roster form by listing all elements that satisfy the condition.

Example:

Roster → Set-builder

A = {2, 4, 6, 8}

A = {x | x is an even natural number less than 10}

Roster form:

A = {2, 4, 6, 8}

Set-builder form:

A = {x | x is an even natural number less than 10}

Set-builder form :

A = {x | x ∈ N, x is even and x < 10}

How to read it

A = {x | x ∈ N, x is even and x < 10}

Read as:

“A is the set of all x such that x belongs to natural numbers, x is even, and x is less than 10.”

Another example

Roster form:

B = {1, 3, 5}

Set-builder form:

B = {x | x ∈ N, x is odd and x < 6}

Important points to remember

|is read as “such that”∈means belongs toConditions are separated using commas or logical words like and

Always mention the base set (

N,Z,R) when possible

Conversion from Set-Builder Form to Roster Form

In this conversion, we list all elements that satisfy the given condition in the set-builder form and write them inside curly brackets.

First, understand the base set mentioned after the belong-to symbol.

Apply the given condition one by one.

Write only those elements that satisfy all conditions.

Do not include repeated elements.

Example 1

Set-builder form:

A = {x | x ∈ N, x < 5}

Roster form:

A = {1, 2, 3, 4}

Example 2

Set-builder form:

B = {x | x ∈ N, x is even and x ≤ 10}

Roster form:

B = {2, 4, 6, 8, 10}

Example 3

Set-builder form:

C = {x | x ∈ Z, −2 ≤ x ≤ 3}

Roster form:

C = {−2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3}

Cardinality of Set

The cardinality of a set is the number of elements present in the set. It is used to measure the size of a set and is denoted by vertical bars on both sides of the set name.

Cardinality is denoted by

|A|, where A is a set.If a set has a fixed number of elements, its cardinality is a natural number.

Cardinality helps in comparing sizes of two sets.

Two sets are equivalent if they have the same cardinality.

Cardinality is used to classify sets as finite, infinite, countable, or uncountable.

Examples

Example 1:

A = {1, 2, 3, 4}

|A| = 4

Example 2:

B = {a, e, i, o, u}

|B| = 5

Example 3 (Empty set):

A = ∅

|A| = 0

Example 4 (repeating elements):

B = {1, 2, 2, 3, 3}

B = {1, 2, 3}

|B| = 3

Important formulas

If A is a finite set with n elements, then

|A| = nCardinality of empty set:

|∅| = 0Cardinality of power set:

If|A| = n, then|P(A)| = 2ⁿ

Special cases

A finite set always has a finite cardinality.

An infinite set has infinite cardinality.

Two sets A and B are equivalent if

|A| = |B|.

Operations on Set

These four are the main operations on sets.

Union (A ∪ B)

Intersection (A ∩ B)

Difference (A − B, B − A)

Complement (A′ or Aᶜ)

Union of Sets

The union of two sets A and B is the set that contains all elements which belong to A or B or both. It is denoted by A ∪ B.

Union includes all elements from both sets.

Common elements are written only once.

Union does not allow repetition.

Union of sets is always a subset of the universal set.

Formula:

A ∪ B = {x | x ∈ A or x ∈ B}

Example:

A = {1, 2, 3}

B = {3, 4, 5}

A ∪ B = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

Intersection of Sets

The intersection of two sets A and B is the set that contains only the common elements present in both A and B. It is denoted by A ∩ B.

Intersection includes only common elements.

If no common element exists, the intersection is an empty set.

Intersection of sets is always a subset of both sets.

Formula:

A ∩ B = {x | x ∈ A and x ∈ B}

Example:

A = {1, 2, 3}

B = {3, 4, 5}

A ∩ B = {3}

Difference of Sets

The difference of two sets A and B is the set of elements that belong to A but do not belong to B. It is denoted by A − B.

Difference depends on the order of sets.

A − B is not equal to B − A.

Elements common to both sets are removed.

Formula:

A − B = {x | x ∈ A and x ∉ B}

Example:

A = {1, 2, 3}

B = {3, 4, 5}

A − B = {1, 2}

B − A = {4, 5}

Complement of a Set

The complement of a set A is the set of elements that belong to the universal set but do not belong to A. It is denoted by A′ or Aᶜ.

Complement is always defined with respect to a universal set.

A ∪ A′ = U

A ∩ A′ = ∅

Formula:

A′ = {x | x ∈ U and x ∉ A}

Example:

U = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

A = {1, 2, 3}

A′ = {4, 5, 6}

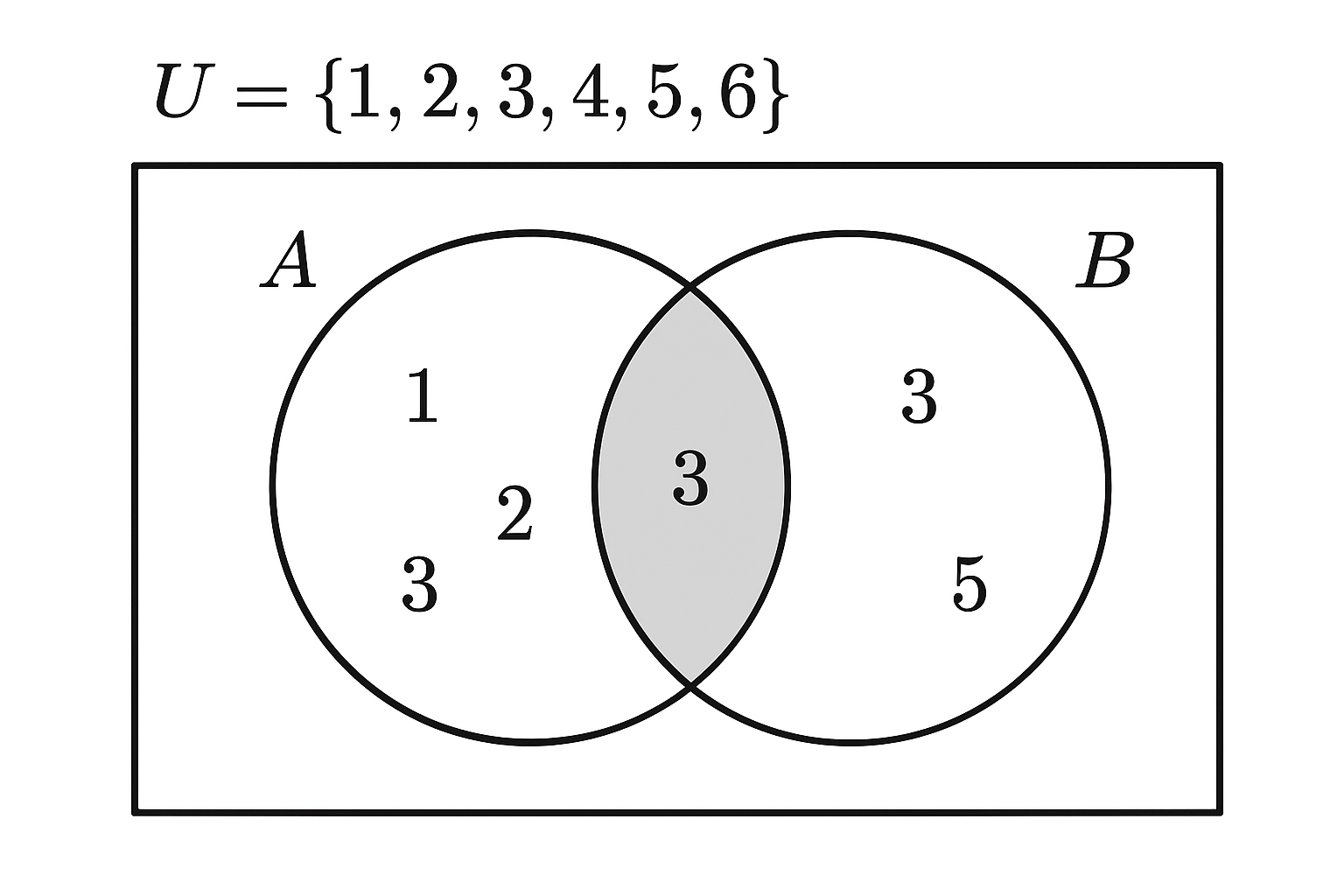

Venn Diagram

A Venn diagram is a pictorial representation of sets using closed curves, usually circles, to show the relationship between different sets within a universal set.

Venn diagrams are used to visually represent sets and their relationships.

The universal set is represented by a rectangle.

Sets are represented by circles inside the universal set.

Overlapping regions show common elements between sets.

Non-overlapping regions show distinct elements.

Venn diagrams are very useful for understanding operations on sets.

Uses of Venn Diagram

To show union of sets.

To show intersection of sets.

To show difference of sets.

To represent complement of a set.

To solve word problems related to sets.

Example

Let

U = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

A = {1, 2, 3}

B = {3, 4, 5}

Common element (A ∩ B) = {3}

Only in A = {1, 2}

Only in B = {4, 5}

Laws of Set Operations

The laws of set operations explain how union, intersection, and complement behave when applied to sets. These laws are used to simplify set expressions and to prove equality of sets in discrete mathematics.

Commutative Law

This law states that changing the order of sets does not change the result.

A ∪ B = B ∪ A

A ∩ B = B ∩ A

Example:

A = {1, 2}, B = {2, 3}

A ∪ B = {1, 2, 3} = B ∪ A

A ∩ B = {2} = B ∩ A

Associative Law

This law states that grouping of sets does not affect the result.

(A ∪ B) ∪ C = A ∪ (B ∪ C)

(A ∩ B) ∩ C = A ∩ (B ∩ C)

Example:

A = {1}, B = {2}, C = {3}

(A ∪ B) ∪ C = {1, 2, 3}

A ∪ (B ∪ C) = {1, 2, 3}

Distributive Law

This law shows how union and intersection distribute over each other.

A ∪ (B ∩ C) = (A ∪ B) ∩ (A ∪ C)

A ∩ (B ∪ C) = (A ∩ B) ∪ (A ∩ C)

Example:

A = {1}, B = {1, 2}, C = {1, 3}

B ∩ C = {1}

A ∪ (B ∩ C) = {1}

(A ∪ B) ∩ (A ∪ C) = {1}

Identity Law

This law states that empty set and universal set act as identity elements.

A ∪ ∅ = A

A ∩ U = A

Example:

A = {1, 2}

A ∪ ∅ = {1, 2}

A ∩ U = {1, 2}

Domination (Null) Law

This law states that union with universal set and intersection with empty set give fixed results.

A ∪ U = U

A ∩ ∅ = ∅

Example:

A = {1, 2}

A ∪ U = U

A ∩ ∅ = ∅

Idempotent Law

This law states that repeating the same set does not change the result.

A ∪ A = A

A ∩ A = A

Example:

A = {1, 2}

A ∪ A = {1, 2}

A ∩ A = {1, 2}

Complement Law

This law explains the relation between a set and its complement.

A ∪ A′ = U

A ∩ A′ = ∅

Example:

U = {1, 2, 3, 4}

A = {1, 2}

A′ = {3, 4}

A ∪ A′ = U

A ∩ A′ = ∅

Double Complement Law

This law states that taking complement twice returns the original set.

(A′)′ = A

Example:

A = {1, 2}

A′ = {3, 4}

(A′)′ = {1, 2}

Absorption Law

This law shows how a set absorbs another set in certain operations.

A ∪ (A ∩ B) = A

A ∩ (A ∪ B) = A

Example:

A = {1, 2}, B = {2, 3}

A ∩ B = {2}

A ∪ (A ∩ B) = {1, 2} = A

De Morgan’s Laws

De Morgan’s Laws describe the relationship between union, intersection, and complement of sets. These laws explain how the complement of a union or intersection can be expressed in terms of complements of individual sets.

De Morgan’s Laws consist of the following two identities:

First De Morgan’s Law

(A ∪ B)' = A' ∩ B'Second De Morgan’s Law

(A ∩ B)' = A' ∪ B'

These laws show that taking complement reverses the operation: union becomes intersection and intersection becomes union.

Proof of First De Morgan’s Law

(A ∪ B)' = A' ∩ B'

Proof:

Let x be any element. [ we take an arbitrary element x from the universal set.]

x ∈ (A ∪ B)'

⇒ x ∉ A ∪ B

⇒ x ∉ A and x ∉ B

⇒ x ∈ A' and x ∈ B'

⇒ x ∈ A' ∩ B'

⇒ (A ∪ B)' ⊆ A' ∩ B'

Now, conversely,

Let x ∈ A' ∩ B'

⇒ x ∈ A' and x ∈ B'

⇒ x ∉ A and x ∉ B

⇒ x ∉ A ∪ B

⇒ x ∈ (A ∪ B)'

⇒ A' ∩ B' ⊆ (A ∪ B)'

Since both sets are subsets of each other,

(A ∪ B)' = A' ∩ B'

✔ Hence proved.

Explanation of First De Morgan’s Law

(A ∪ B)' = A' ∩ B'

The first De Morgan’s law talks about the complement of the union of two sets. The union A ∪ B contains all elements that belong to set A or set B.

When we take the complement of this union, we are selecting elements that do not belong to A ∪ B. This means the element is not in A and also not in B.

Now, if an element is not in A, it must belong to the complement of A, which is A′. Similarly, if an element is not in B, it must belong to the complement of B, which is B′.

Since both conditions must be true at the same time, the element belongs to both A′ and B′. Belonging to both complements means the element is in the intersection A′ ∩ B′.

Therefore, the complement of the union of two sets is equal to the intersection of their complements.

Proof of Second De Morgan’s Law

(A ∩ B)' = A' ∪ B'

Proof:

Let x be any element. [ we take an arbitrary element x from the universal set.]

x ∈ (A ∩ B)'

⇒ x ∉ A ∩ B

⇒ x ∉ A or x ∉ B

⇒ x ∈ A' or x ∈ B'

⇒ x ∈ A' ∪ B'

⇒ (A ∩ B)' ⊆ A' ∪ B'

Now, conversely,

Let x ∈ A' ∪ B'

⇒ x ∈ A' or x ∈ B'

⇒ x ∉ A or x ∉ B

⇒ x ∉ A ∩ B

⇒ x ∈ (A ∩ B)'

⇒ A' ∪ B' ⊆ (A ∩ B)'

Since both sets are subsets of each other,

(A ∩ B)' = A' ∪ B'

✔ Hence proved.

Explanation of Second De Morgan’s Law

(A ∩ B)' = A' ∪ B'

The second De Morgan’s law explains the complement of the intersection of two sets. The intersection A ∩ B contains only those elements that belong to both A and B together.

When we take the complement of this intersection, we are choosing elements that are not common to both sets. This happens when an element is not in A or not in B. If an element is not in A, then it belongs to the complement A′. If it is not in B, then it belongs to the complement B′.

In this case, it is enough for the element to be outside at least one of the sets, so we use the union operation. Therefore, all elements that are not common to A and B belong to A′ ∪ B′.

Hence, the complement of the intersection of two sets is equal to the union of their complements.

Conceptual Explanation (Easy to Understand)

A ∪ B means elements that are in A or B or both

(A ∪ B)' means elements that are not in A and not in B

“Not in A and not in B” is exactly A' ∩ B'

Similarly,

A ∩ B means elements that are in both A and B

(A ∩ B)' means elements that are not in both

“Not in both” means either not in A or not in B

That is A' ∪ B'

All Important Formulas of Sets

Basic Symbols

Belongs to: x ∈ A

Does not belong to: x ∉ A

Empty set: ∅

Universal set: U

Cardinality: |A|

Subset and Superset

A ⊆ B → A is subset of B

A ⊂ B → A is proper subset of B

A ⊇ B → A is superset of B

A ⊃ B → A is proper superset of B

Operations on Sets

Union

A ∪ B = { x | x ∈ A or x ∈ B }

Intersection

A ∩ B = { x | x ∈ A and x ∈ B }

Difference

A − B = { x | x ∈ A and x ∉ B }

Complement

A′ = { x | x ∈ U and x ∉ A }

Cardinality

|∅| = 0

If A has n elements, then |A| = n

Power set: |P(A)| = 2ⁿ

Laws of Sets

Idempotent Laws

A ∪ A = A

A ∩ A = A

Commutative Laws

A ∪ B = B ∪ A

A ∩ B = B ∩ A

Associative Laws

(A ∪ B) ∪ C = A ∪ (B ∪ C)

(A ∩ B) ∩ C = A ∩ (B ∩ C)

Distributive Laws

A ∪ (B ∩ C) = (A ∪ B) ∩ (A ∪ C)

A ∩ (B ∪ C) = (A ∩ B) ∪ (A ∩ C)

Identity Laws

A ∪ ∅ = A

A ∩ U = A

Domination Laws

A ∪ U = U

A ∩ ∅ = ∅

Complement Laws

A ∪ A′ = U

A ∩ A′ = ∅

(A′)′ = A

Absorption Laws

A ∪ (A ∩ B) = A

A ∩ (A ∪ B) = A

De Morgan’s Laws

(A ∪ B)′ = A′ ∩ B′

(A ∩ B)′ = A′ ∪ B′

Difference Laws (Often asked in MCQs)

A − B = A ∩ B′

A − (B ∪ C) = (A − B) ∩ (A − C)

A − (B ∩ C) = (A − B) ∪ (A − C)

Disjoint and Mutually Disjoint

A and B are disjoint ⇔ A ∩ B = ∅

{A₁, A₂, …} mutually disjoint ⇔ Aᵢ ∩ Aⱼ = ∅ for i ≠ j

Venn Diagram Logic

Union → shade both circles

Intersection → shade common part

Difference → shade only first set

Complement → shade outside set

Cartesian Product of Sets

The Cartesian product of two sets A and B is the set of all ordered pairs where the first element comes from set A and the second element comes from set B. It is denoted by A × B and is used as the base concept for defining relations and functions.

An ordered pair is written as (a, b).

Order of elements matters in an ordered pair means, (a, b) ≠ (b, a) unless a = b.

The Cartesian product can be formed only between sets.

Cartesian product is mainly used to define relations.

Mathematical representation

Let A and B are two sets.The cartisian product of A and B denoted by A×B ,is the set of all ordered pairs (a,b) , where a ∈ A and b ∈ B

A × B = { (a, b) | a ∈ A and b ∈ B }

Example 1

Let

A = {1, 2}

B = {a, b}

Then,

A × B = { (1, a), (1, b), (2, a), (2, b) }

Example 2 (order matters)

Let

A = {1, 2}

B = {3}

A × B = { (1, 3), (2, 3) }

B × A = { (3, 1), (3, 2) }

So,

A × B ≠ B × A (Not Commutative)

Cardinality of Cartesian Product

If set A has m elements and set B has n elements

|A| = m and |B| = n

Then, A × B has m × n number of ordered pairs

|A × B| = m × n or mn

Example (cardinality)

Let

A = {1, 2, 3}

B = {a, b}

|A| = 3, |B| = 2

So,

|A × B| = 3 × 2 = 6

Special cases

If A = ∅ or B = ∅, then A × B = ∅

If A has one element and B has n elements, then A × B has n ordered pairs

A × A is called the Cartesian square of A

Properties (Laws) of Cartesian Product

The Cartesian product follows certain rules that describe how it behaves with respect to order, size, and set operations.

1. Order of Sets (Not Commutative)

The Cartesian product is not commutative.

This means:

A × B is generally not equal to B × A.

Reason:

In ordered pairs, the position of elements matters.

Example:

A = {1, 2}

B = {a}

A × B = { (1, a), (2, a) }

B × A = { (a, 1), (a, 2) }

So,

A × B ≠ B × A

2. Cardinality Property

The number of ordered pairs in a Cartesian product depends on the sizes of the sets.

If |A| = m and |B| = n

Then, |A × B| = m × n

Example:

A = {1, 2, 3}

B = {x, y}

|A × B| = 3 × 2 = 6

3. Empty Set Property

If at least one of the sets is empty, the Cartesian product is empty.

A × ∅ = ∅

∅ × A = ∅

Reason:

No element is available to form ordered pairs.

4. Equality of Cartesian Products

Two Cartesian products are equal only when:

A = C

B = D

Then:

A × B = C × D

Order must also match.

5. Distributive Property over Union

Cartesian product distributes over union.

A × (B ∪ C) = (A × B) ∪ (A × C)

(B ∪ C) × A = (B × A) ∪ (C × A)

Example:

A = {1}

B = {a}

C = {b}

A × (B ∪ C) = { (1, a), (1, b) }

(A × B) ∪ (A × C) = { (1, a), (1, b) }

6. No Distributive Property over Intersection (Exam trap)

In general: A × (B ∩ C) ≠ (A × B) ∩ (A × C)

This is not always true. So be careful in MCQs.

7. Cartesian Square

If A is a set, then:

A × A is called the Cartesian square of A.

Example:

A = {1, 2}

A × A = { (1, 1), (1, 2), (2, 1), (2, 2) }

Relation

A relation from a set A to a set B is defined as a subset of the Cartesian product A × B. It represents a connection between elements of A and elements of B in the form of ordered pairs, where the first element belongs to A and the second element belongs to B.

A relation is always formed from a Cartesian product.

A relation is a subset, not the whole Cartesian product.

Each element of a relation is an ordered pair (a, b).

The order of elements in a pair is important.

A relation from A to B is written as R ⊆ A × B.

If A = B, the relation is called a relation on A.

Example 1 (Relation from A to B)

Let

A = {1, 2}

B = {a, b}

A × B = { (1, a), (1, b), (2, a), (2, b) }

Let

R = { (1, a), (2, b) }

Then R is a relation from A to B, because every ordered pair of R belongs to A × B.

Example 2 (Relation on a set)

Let

A = {1, 2, 3}

A × A = { (1,1), (1,2), (1,3), (2,1), (2,2), (2,3), (3,1), (3,2), (3,3) }

Let

R = { (1,1), (2,2), (3,3) }

Then R is a relation on A.

Types of Relations

Empty relation

Universal relation

Identity relation

Inverse relation

Reflexive relation

Irreflexive relation

Symmetric relation

Asymmetric relation

Antisymmetric relation

Transitive relation

Equivalence relation

Partial order relation

1. Empty Relation

An empty relation on a set A is a relation that contains no ordered pairs at all. It is a relation where no element of the set is related to any element, including itself.

Let A be any set.

R = ∅

R ⊆ A × A

An empty relation is denoted by R = ∅.

It contains zero ordered pairs.

No element is related to itself or to any other element.

An empty relation can be defined on any set.

An empty relation is not reflexive, because no (a, a) pair exists.

An empty relation is symmetric and transitive by definition (important exam point).

Example

Let

A = {1, 2, 3}

Then,

A × A = { (1,1), (1,2), (1,3), (2,1), (2,2), (2,3), (3,1), (3,2), (3,3) }

Empty relation on A:

R = ∅

No ordered pair from A × A is included in R.

Diagram representation

2. Universal Relation

A universal relation on a set A is a relation that contains all possible ordered pairs of elements of A. In other words, every element of A is related to every element of A, including itself.

Contains all possible ordered pairs from the Cartesian product (R = A × A).

Universal relation is the largest possible relation on a set.

It always includes all self-pairs and all cross pairs.

Universal relation is always reflexive, symmetric, and transitive.

It is the opposite of the empty relation.

If A is a set, then the universal relation R on A is:

R = A × A

Example

Let

A = {1, 2}

Then,

A × A = { (1,1), (1,2), (2,1), (2,2) }

So the universal relation on A is:

R = { (1,1), (1,2), (2,1), (2,2) }

3. Identity Relation

An identity relation on a set A is a relation in which every element of the set is related only to itself and to no other element. It consists of all ordered pairs of the form (a,a) where a belongs to A.

Identity relation contains only self-pairs.

It is a subset of the universal relation.

Identity relation is always reflexive, symmetric, and transitive.

It is different from the empty relation and universal relation.

If A is a set, then the identity relation on A is written as:

I = { (a, a) | a ∈ A }

Example

Let

A = {1, 2, 3}

Then the identity relation on A is:

I = { (1,1), (2,2), (3,3) }

No other ordered pairs are included.

Important exam points

Identity relation contains exactly |A| ordered pairs.

If any pair (a, b) with a ≠ b is present, the relation is not identity.

Identity relation is always defined on the same set.

4. Inverse Relation

If R is a relation from a set A to a set B, then the inverse relation of R is the relation obtained by reversing the order of every ordered pair in R. It is denoted by R⁻¹ and becomes a relation from B to A.

In inverse relation, the domain and range get interchanged.

If (a, b) belongs to R, then (b, a) belongs to R⁻¹.

Inverse relation exists for every relation.

A relation and its inverse are not necessarily the same.

If, R ⊆ A × B

then

R⁻¹ = { (b, a) | (a, b) ∈ R } and R⁻¹ ⊆ B × A

Example

Let

A = {1, 2}

B = {a, b}

Let

R = { (1, a), (2, b) }

Then the inverse relation is:

R⁻¹ = { (a, 1), (b, 2) }

Here, R is from A to B, and R⁻¹ is from B to A.

Diagram representation

Important exam points

Inverse relation reverses all arrows in the diagram.

(R⁻¹)⁻¹ = R

A relation may or may not be equal to its inverse.

5. Reflexive Relation

A relation R on a set A is called a reflexive relation if every element of the set is related to itself, meaning that for each element aaa in A, the ordered pair (a,a) belongs to R.

The relation must be defined on the same set A.

All self-pairs must be present in the relation.

Missing even one self-pair makes the relation not reflexive.

Identity relation is a special case of reflexive relation.

For a relation R on set A:

R is reflexive if

(a,a) ∈ R for all a∈A

Example

Let

A = {1, 2, 3}

Define

R = { (1,1), (2,2), (3,3), (1,2) }

Since all self-pairs (1,1), (2,2), and (3,3) are present,

R is a reflexive relation.